When it comes to reading books, I prefer quality over quantity. And by “quality” I’m referring to an investment of time that lends itself to a depth of understanding and experience.

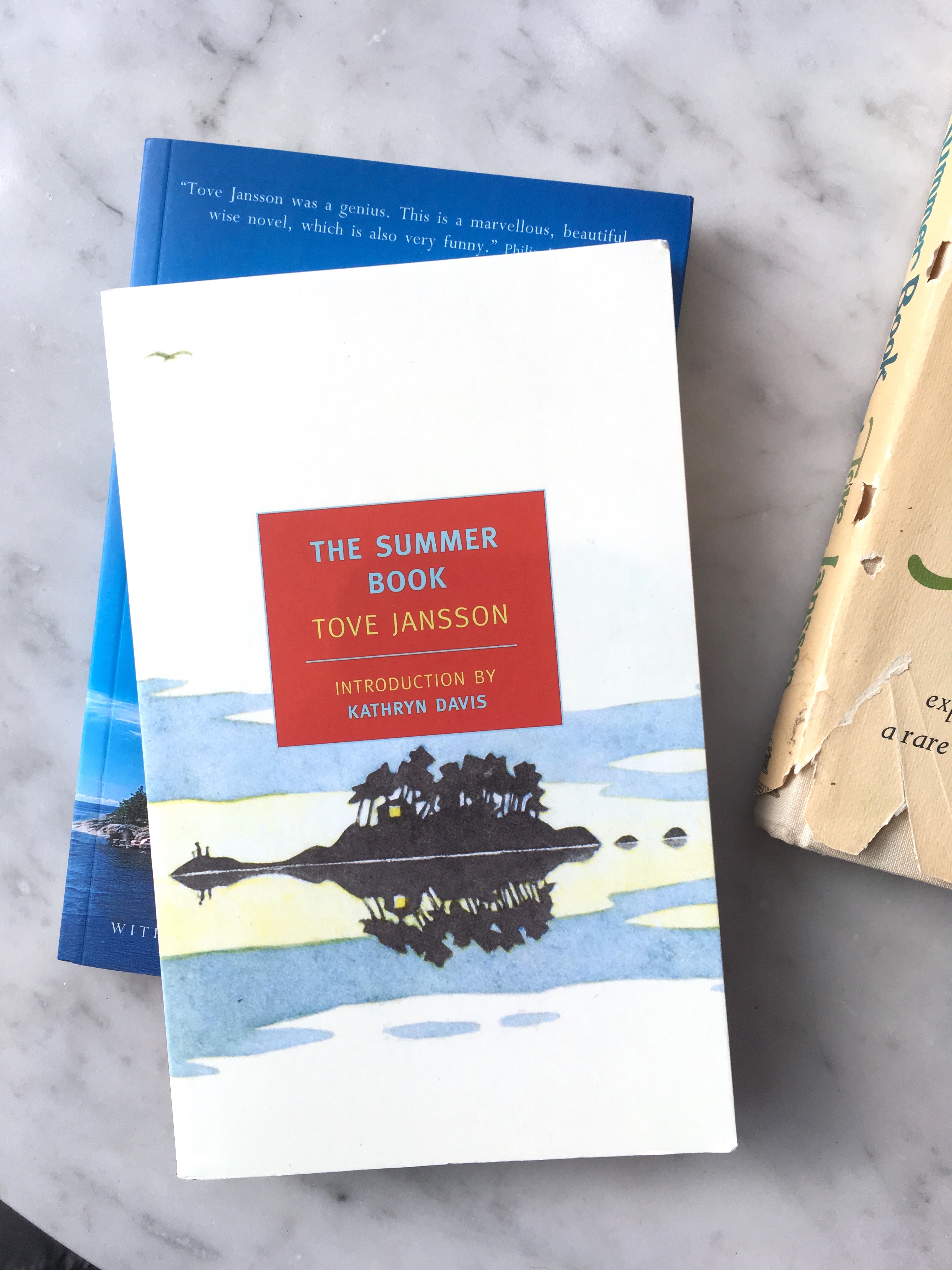

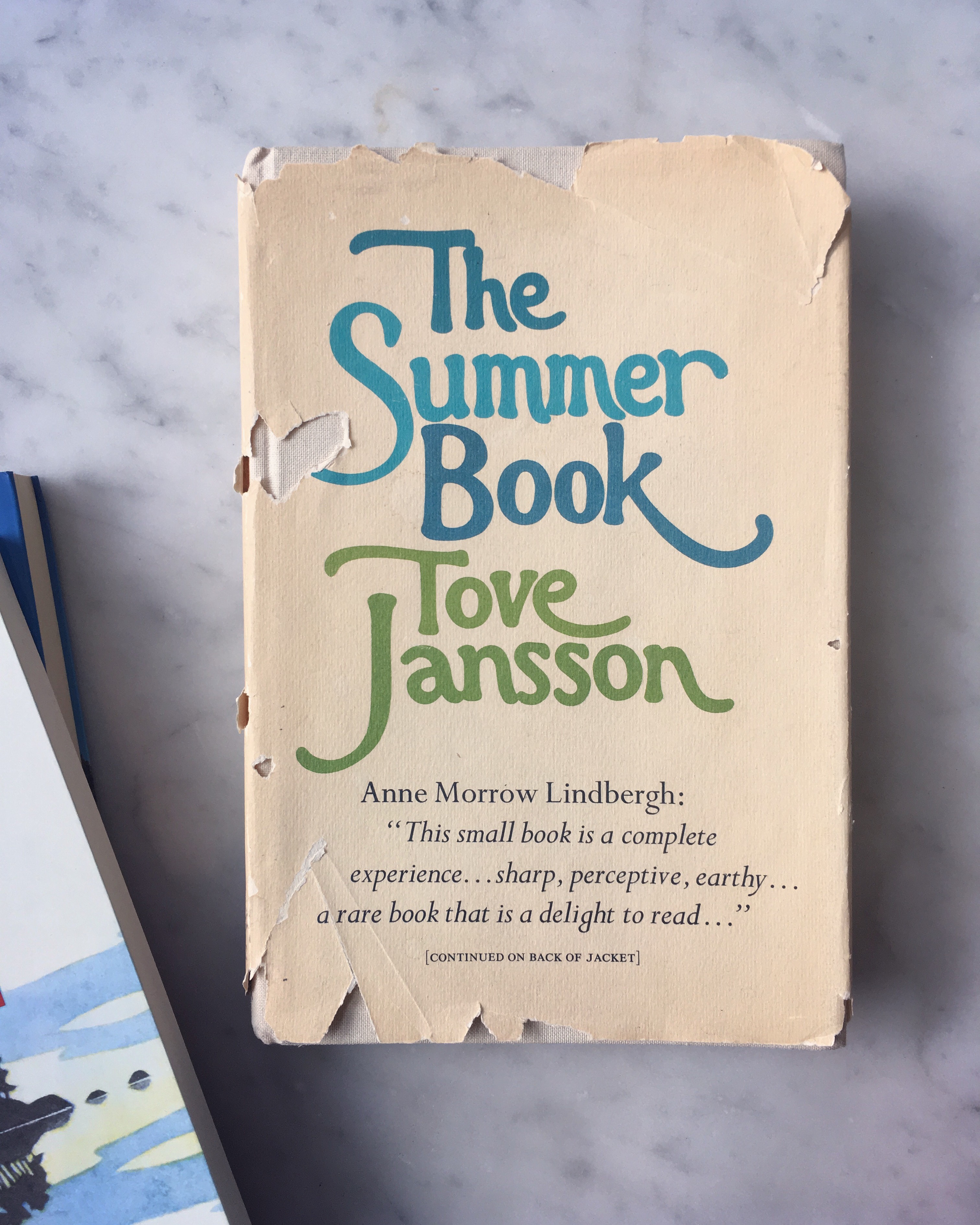

The well-worn volumes on my bookshelves reveal my habit of re-reading those books that resonate with me until they physically come apart in my hands.

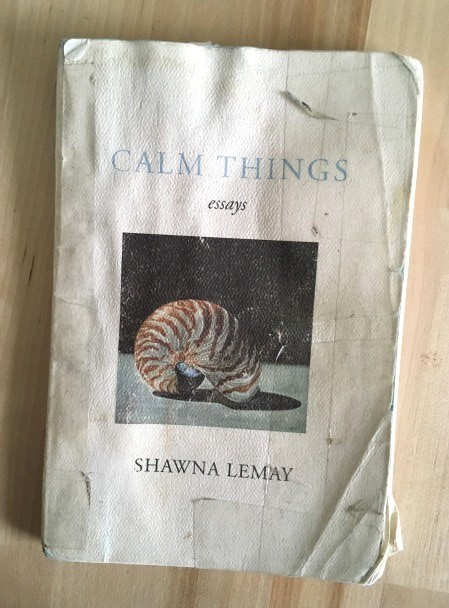

And at the top of this list are Journal of a Solitude by May Sarton, and Calm Things by Shawna Lemay (in addition to works of poetry, prose and non-fiction, Lemay is the author of the sublime blog Transactions with Beauty).

Themes related to solitude and the struggle to carve out time for creative work are central to both writers, and to both books.

I was so fascinated by the rigorous creative life that fills the pages of Calm Things that I carried this book around with me until it was worn to the point that I had to tape it back together and buy a second copy to use as a back-up.

And after my first reading of Journal of a Solitude, I re-read it several times, entry by entry, in a way that made it last all year.

By giving me a window into their lives and creative practices, these writers gave me a tremendous gift — the gift of permission to make room in my own life, without explanation, for the creative pursuits that make me feel most purposeful and fulfilled.

This gift is similar to the gift of unspoken understanding that May Sarton once received from a friend:

Anne Woodson was to have come to lunch today, the only “free day” I shall have for some time to come. When I got back from Cambridge on Wednesday, I walked into a house full of surprises — a hanging fuschia, two marvellous rose plants…and a note from Anne to say that she was giving me a day’s time. (She had come on purpose while I was away.) This is the day she has given me and I have two poems simmering, so I had better get to work.

From Journal of a Solitude by May Sarton